We open our columns to talented new voices, who can send in (short) stories.

The first one is a short story by Eduardo Riccardo. It was some 30 pages he said, but now he tells us 'it would be more something like 50, even 60'. Hm. Okay. Only because we pity guys living on goat's milk and mountain herbs.

We publish it the old fashioned 19th century way: episodically.

(Part 12.)

“You don’t understand, Ben. You have to help me.”

“Wait, i’ll turn on the lights. Goddamn Rebecca, where is the nightlight? What did you do with it? Why aren’t you in bed?” He doesn’t like things getting out of hand, not in the daytime and surely not at night. He’s desperately trying to restore order. He’s still tapping the blanket.

“Please don’t shout, Ben. And for God’s sake don’t turn on the lights!” He can’t believe his ears. The girl without tears seems to be sobbing.

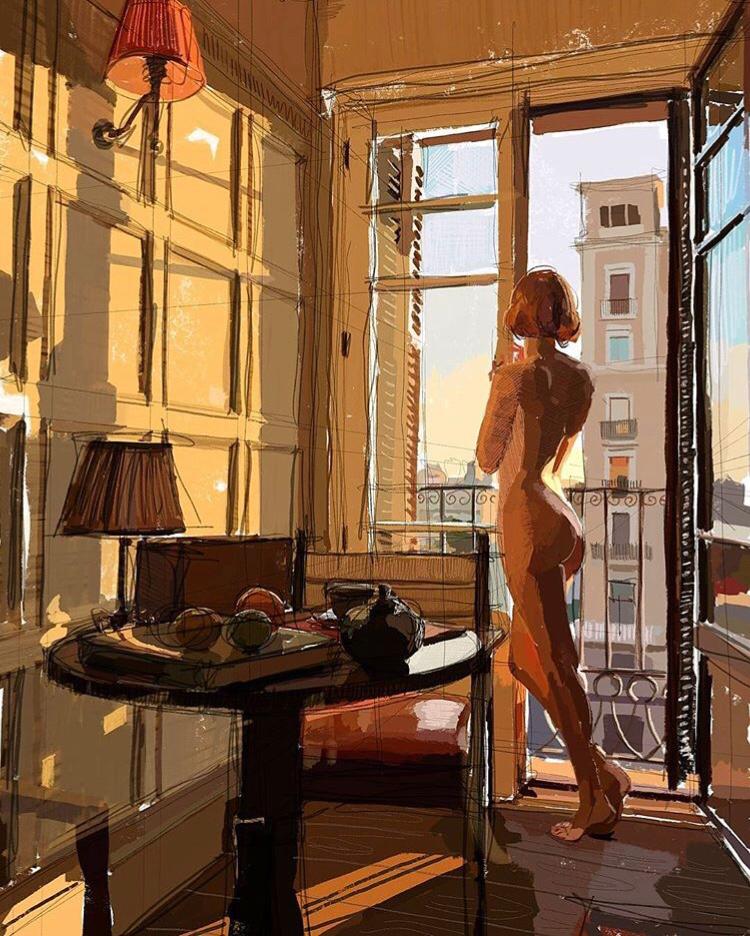

“Oh darling,” he says. “You’re sobbing. Why?” Grief overwhelming him. He’s almost there. In his hands her nightgown, soft, satin, a lace border. She’s taken it off, she’s standing naked in the dark. He presses his face into the nightgown. “Oh darling,” he repeats, “please come here. It’s too cold out there, come with me, under the blankets.” He puts the nightgown down. He’s longing for her, he feels ridiculous, sitting on this mattress alone, all excited, not knowing what to do. He doesn’t even know where to crawl to. And he still can’t find the night lamp. “Come here, honey.”

“I’m not sobbing,” she says, her voice steady again, reprimanding even. “Why did you say i’m sobbing? Don’t say that because i’m not.”

“But you were, honey, you were.”

“No I was not.” She’s bumping against the bed. He finds her leg, then another one; then her hands. She’s searching for the sheets, then crawling beneath them, hiding, pushing him away.

“What is it about your feet?” he asks. He feels her warmth. She’s shivering though.

“Please don’t start about my feet,” she says. “I’m not lying here for you to start whining about my feet. There’s nothing wrong with them. Just don’t focus on my feet.”

I’ll warm them,” he says. He goes down, reaching for them, to hold them in his hands and warm them.

“DON’T TOUCH THEM, YOU IDIOT,” she shouts. She’s holding him by the wrists. Silence. They lay panting for a while.

“Anyway, it’s only my right one.”

The next morning he hears her stumbling down the stairs, onto the terrace, in her pyjamas. She’s sitting at the small round grey hardwood table, rubbing her eyes, looking indifferently at the breakfast he’s prepared her: brown bread, scrambled eggs, he’s pressed eight oranges too. She looks rumpled up. The sun is hiding; a big cloud passing by. Shivering she pulls up her knees, then puts her arms around them.

He brings the warm Camembert, she’s fond of it. They kiss.

“I love you, Ben,” she says. “You know that, don’t you?” He nods.

“Of course I do, darling.”

“We’re having a great time, no?” she asks. He looks at her, her left cheek is still a little pink. It’s the side she’s been lying upon all night, his knees bent into the crooks of hers, his arms around her. Her hair is a mess, blonde tails running over her nose, eyes, lips. Her nightgown hanging open, her skin ivory, smooth.

“I do anyway,” she says. “I feel as if I belong here, you know. This is my home. We’re going to be together for a long, long time, isn’t it darling?” She shoves her chair backwards, kisses his neck, bites his ear. “Aren’t we?"

In the distance waves rolling in, the screeching of gulls. A breeze springing up, blowing her hair over her eyes. She sits erect, a coffee spoon in one hand, the other resting on her thigh. He’s softly draping her curls behind her ear with his fingers, raising the pink blush and her smile.

After breakfast they’re having more coffee, she’s showing pictures of her dad, who emigrated to Brazil twelve years ago. She misses him, she says. “It’s almost unbelievable, but still, I do.” He was a salesman: coffee and minerals, and in fact everything, as long as it came from Brazil.

“When I was a kid I thought Brazil was some country in outer space. Pluto was only halfway. The way he talked about it, it had mythical status. It could as well have been located next to Atlantis.”

Her mum had told her what happened. Not a very reliable source of information, but on this she believed her. On one of his missions dad had been sitting alone in a bar downtown Sao Paulo, having a caipirinha on the rocks. It had been the hottest day of the year, he had been driving around in an old Buick without airco. Rolling down the windows made it even worse - that kind of day. Suddenly this girl approached him, Consuela. She hadn’t been discouraged by the big circles under his armpits. She’d asked him straight away if she could have a sip of his cocktail. He didn’t understand, her English was awful. She was quite short, athletic. A proud posture, black hair, five, six rings at her fingers. Sharp nose. Her dad liked sharp noses.

“Mine is sharp too now, don’t you think, darling?”

“You would have made Cleopatra jealous,” he says. He’s thinking about the pictures she showed couple of weeks earlier, and about the fight. About her mother. And about René too. Maybe René had paid for the nose.

“I hope so,” she says, “because all this Cleopatra stuff is bollocks. Her nose was ugly. It’s been proven by anthropologists. My esthetical surgeon told me so. Mine is much, much prettier. Not perfect, but still.”

She yawns. Her nightgowns falls open. The sun caressing her belly.

“Sunshine is beneficial to the baby’s psychological welfare,” she says. “Anyway – Brazil. Consuela asking for a sip, pointing at the glass; then her ring finger gliding over the rim. Smiling; she had beautiful, very white teeth. As if it belonged to her cabinet of basic instruments she took a straw out of her pocket. A light green one. Dad told her it was his favourite colour. She giggled and looked as if he was telling this to draw her near, as if he was flirting with her, but it wasn’t: green really was his favourite colour he said, so she started giggling even louder. She put her straw in the glass and drank half of it, like it was lemonade. Then, putting her cold fingers in his neck she tells him he’s very kind, and that in return he deserves something very special. Really special. Suddenly, out of the blue, she kisses him. Not just a short kiss, like this – no, a long one. One that lasts for let’s say fifteen seconds, leaving my dad breathless.” That very moment her dad knew he would never love any other woman again, never ever, - not like this.

“Love at first kiss. Romantic.”

“Are you cynical now, Ben? One doesn’t have to get cynical over this, you know.”

“But I’m not, darling.”

They’d had another caipirinha, her dad and his Consuela, then she had taken him by the hand, “I have to show you something. A surprise.” Meanwhile pulling him into the toilets. “The limbo of hell, really, a ghastly odour everywhere.” Still giggling she had pushed him through one of the doors, ripping open the white shirt he was wearing, shaking off one of her cheap sandals, putting her bare foot against the wall above the toilet pot, zipping open his fly. He had protested, had whispered he’d wanted to talk about it, he’d wanted to get to know her better. As if he already knew anything about her. “I’ll let you know everything, senhor,” she said, “everything. Everything! Trust me, senhor.” She almost took him like a man; he couldn’t resist; after what seemed to him no more than ten seconds he came.

Two months later they had been married, and the next year her half-sister had been born, Daphne, named after the sheep herding girl in Bernini’s statue.

The week after their second wedding anniversary she had been accompanying Consuela to town, buying baby clothing for Daphne. A day that changed her life. When they came back home they ran through the house, arms full of bags, shouting, elated, brimming over with merriment. Actually, she liked Consuela a lot. Pushing open the back door. Her dad lying on a lounger, enjoying the sunshine, so it seemed. Fully clothed, what was strange.

The doctors told them he hadn’t suffered. Nor even felt anything. It had happened in a second. He was there, and the next he wasn’t anymore. He had only been sixty-two.”

“As old as René,” he says. The next moment he’s sorry for saying this. But it’s like she’s ignoring it. She just nods, the cracking sound of crunched toast evaporating in the summer sky.